The byzantine bureaucracy of U.S. government regulations on “chemical safety” at thousands of facilities across the country has led to potential security “gaps” — gaps through which clever terrorists could slip and do severe damage, according to a new government watchdog report.

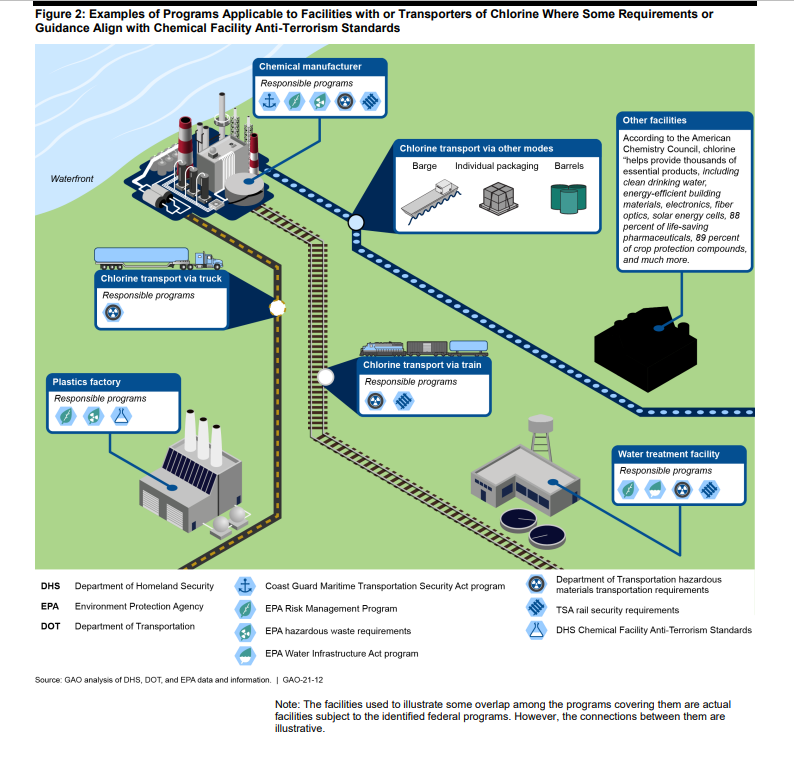

The report, published by the Government Accountability Office last week, focused on the overlapping regulations handed down from eight different federal agencies whose rules apply to different facilities. Hundreds of facilities are subject to overlapping policies, while others don’t have to abide by the same security standards, creating a confusing, uneven playing field for protecting the U.S. homeland.

“The United States has thousands of facilities that produce, use, or stores hazardous chemicals that, if not properly safeguarded, could be used by terrorists to inflict mass casualties and damage,” the report says. “These chemicals, if released from a facility, stolen, or diverted and used to create explosive devices, chemical weapons, or other weapons, could cause significant harm to surrounding populations.”

The principle program that regulates dangerous chemicals in the U.S. is the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards initiative, launched by the Department of Homeland Security in 2006. It essentially says that any facility holding a significant amount of dangerous chemicals has to be reviewed by investigators, assigned a risk level, and then must implement security measures commiserate with that risk level.

But as the GAO report notes, hundreds of facilities are subject to various other safety and security regulations as well, which leads to needless duplication. For example, like CFATS, six of the other eight programs require the development of an emergency response plan. (Only three require an effort to “deter cyber sabotage.”)

Perhaps most concerning, however, is that some facilities, like water and wastewater facilities, aren’t subject to CFATS, even though they store a lot of dangerous chemicals.

“For example, there are about 150,000 public water systems and over 25,000 wastewater treatment works that are excluded from the CFATS program, according to EPA’s data,” the report says. Elsewhere the report cited a previous working group’s conclusion that those kinds of facilities “may present attractive terrorist targets due to their large stores of potentially high-risk chemicals and their proximities to population centers.”

The report notes that those facilities do have other security regulations in place, and it says that DHS believes they’re of “tangential security value,” even though “in most cases, these facilities are not required to implement security measures commensurate to their level of security risk.”

Overall, GAO said it made seven recommendations, including asking the various federal agencies to identify facilities subject to overlapping regulations and suggesting DHS and EPA conduct security assessments where gaps might exist.

GAO said the federal agencies generally agreed with their recommendations — except the EPA, which took issue with the idea it needed to work with DHS to identify security gaps. That’s because, as EPA Associate Deputy Administrator Doug Benevento put it, EPA had already done that and made Congress aware of the potential gaps as far back as the George W. Bush administration.

PRIMARY SOURCE: Overlapping Programs Could Better Collaborate to Share Information and Identify Potential Security Gaps (GAO.gov)

[Do you have a tip or question for Code and Dagger? Send it along at CodeAndDagger@protonmail.com. And if you like what you read and want to help keep the site running (kind of) smoothly, click here to learn how you can lend your support.]